Since 1989, after Russia ceased military operations in the Afghanistan conflict, there was a period of reflection and soul searching amongst the country’s military and political leadership – not unlike the post-Vietnam era for the United States. Afghanistan was a quagmire: as Russia discovered and then the eastern powers realised in their failure at the hands of a vicious insurgency. While this period, between roughly 2001 to 2021 for western forces in Afghanistan and Iraq radically transformed western military doctrine, tactics, and equipment, the Russians were embroiled in their own post-Afghanistan conflicts and had begun to embrace cyber capabilities in several powerful ways.

The Chechen conflict began in 1994, and then after a lull was reignited in 2009. That provided a battleground in which to apply the hard lessons learned in fighting an insurgency. In the Second Chechen War, from 1999 to 2007, Moscow effectively insulated the Russian information space from outside influence – this included information warfare capabilities to ensure the public remained supportive of the conflict. [1] Then, in 2008, Russia invaded Georgia, specifically South Ossetia and Abkhazia, catching NATO off-guard with sudden cyber-attacks which were only hinted at by the Estonian DDoS attacks conducted the previous year.

The Russian invasion of Georgia was the first war in history in which cyber warfare coincided with military action and for the first-time cyber forces – supported by potentially outsourced or conscripted Russian cyber criminals – became part of the cyber force.[2] What we do know from public statements is that Russia’s “General Staff Main Intelligence Directorate’s (GRU) Main Centre for Special Technologies (GTsST, also known as Unit 74455 and Sandworm) carried out a widespread disruptive cyber-attack against the country of Georgia.[3] We are not certain exactly who was wearing uniforms. What we do know is the first wave of cyber-attacks launched against Georgian media sites were in-line with tactics that had been used in military operations: “cyber seizure” of the internet equivalent of TV and radio stations, regarded as the key sources of information for the citizens of Georgia.

Clearly, the Russians felt they were onto something – seeing cyber-attacks as not just a tool of foreign policy and espionage but now a “force multiplier” on the battlefield, equally useful as a tool of destabilization, disinformation and evolving their capabilities to include widespread and destructive cyber-attacks such as Not Petya and Bad Rabbit.

Operation “Armageddon”, a Russian campaign of systematic cyber-espionage on the information systems of government agencies, law enforcement, and defence agencies, began in 2013. The information obtained in this way could probably help Russia on the battlefield. The victims of Russian cyber-attacks were government agencies in Ukraine, the EU and US, defence agencies, international and regional defence, and political organizations, think tanks, the media, and dissidents.

In February 2014, according to then director of the US National Security Agency, Michael Rogers, with the start of a military incursion into Crimea Russia also launched a cyber war against Ukraine to damage such important infrastructure as telecommunications and government networks. Ukrainian experts also state the beginning of a cyberwar with Russia. By March 2014, as Russian troops entered Crimea communication centres were raided and Ukraine’s fibre optic cables were tampered with, cutting connection between the peninsula and mainland Ukraine. [4]Additionally Ukrainian government websites, news and social media were shut down or targeted in DDoS attacks, while the mobile phones of many Ukrainian parliamentarians were hacked or jammed. [5]

The Russian-Ukrainian cyberwar was the first conflict in which a successful cyber-attack on the energy network was carried out. The attack brought down the Ukrainian grid on 23 December 2015. The result was power outages for roughly 230,000 consumers in Ukraine for as much as 6 hours.

According to the US Presidential Administration, the malware attack on Ukraine by Russia in June 2017 using the NotPetya virus became one of the most successful and destructive cyber-attacks to date. Both arms of Russian offensive cyber capability have played a role: APT29, Russia’s Foreign Intelligence Service, known as SVR (also known as Cozy Bear, Cozy Duke); and APT28, the GRU’s 6th Directorate/Military Intelligence/Russian Army (also known as Sofacy Group, Tsar Team, Pawn Storm, Fancy Bear).

Both the 2008 Georgian invasion and occupation, and the 2014 Ukraine invasion and occupation, followed similar formulas leading to successful military operations which achieved foreign policy objectives. The concept of Russian cyber operations in support of military objectives to achieve key foreign policy objectives was now part of a “text-book” operation.

When Russia tried to apply the same approach in the 2015 Syrian civil war, however, there was a major problem: the Syrian war was not an invasion and occupation of an area of a country with a sympathetic ethnically or politically aligned Russian minority. It was a military intervention in support of a deeply unpopular regime in a country which had been ravaged by a brutal civil war since Assad attempted to crush Arab Spring protests in 2011, dragging in numerous protagonists and proxy groups. The Syrian Civil War is a complex conflict. Although the main combat is between the Syrian government and the opposition, the proxy war between foreign actors, and non-state actors adds an additional dimension to the conflict.

Understanding cyber conflict can easily be broken down into three offensive categories: disinformation campaigns, espionage campaigns, and destructive cyber-attacks. Within each of these categories exists a particular type of attack: in support of broader foreign policy objectives and/or in direct support of military objectives. The struggle between the Free Syrian Army (FSA) and the Assad regime was intensified as the narrative of both groups played out online. But there was a new development which immensely complicated both sides struggle.

In an article by Bryan Lee in The Small War Journal, he concludes:

Lastly, the use of cyber capabilities in Syria has allowed non-state actors and even non-combatants to engage in the war effort. Groups, like Anonymous, and even individuals who are not even located in Syria, are now able to participate in the cyber dimension of the war. As a result, cyber capabilities have effectively eliminated geographical barriers to warfare allowing any person who has an interest in Syria to participate in the war effort.

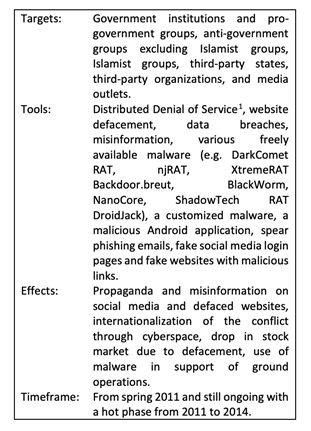

In the CCS CSS CYBER DEFENSE PROJECT’s analysis of the use of “cyber tools in an internationalized civil war context”, the scale and complexity of cyber activities in the Syrian conflict are outlined in a useful table:

Russia began mounting a far-reaching cyber espionage campaign against Syrian opposition groups and NGOs in 2016. “The Syrian cyber-attacks are mounted using fake replicas of legitimate organisations’ websites, which infect computer users when they are accessed. They also involve crafting cleverly disguised emails with malign attachments designed to look like trusted personal correspondences, press releases or official notices.” It is alleged that Russia supported the Syrian regime indirectly by launching DDoS attacks against Turkish websites to retaliate against the shooting down of a Russian plane by the Turkish air force. APT28 defaced the French television channel TV5 Monde with pro-ISIS messages in what appears to be a standard web defacement attack.

It comes as no surprise that the SFA used cyber capabilities to obtain a tactical advantage on the battlefield. Rebel fighters are known to use online applications, like Google Maps, to locate targets and calibrate long-range weapons to strike them. These fighters have also used the internet to coordinate units on the battlefield. The regime, however, has adapted to this tactic by occasionally disrupting the internet and other communications networks ahead of government military offensives.

From late 2014 and through 2016, FANCY BEAR X-Agent implant was covertly distributed on Ukrainian military forums within alegitimate Android application developed by Ukrainian artilleryofficer Yaroslav Sherstuk. The original application enabled artillery forces to more rapidly process targeting data for the Soviet-era D-30 Howitzer employed by Ukrainian artillery forces reducing targeting time from minutes to under 15 seconds. According to Sherstuk’s interviews with the press, over 9000 artillery personnel have been using the application in Ukrainian military.

According to an update provided in March 2017 by the International Institute for Strategic Studies (IISS) Research Associate for Defence and Military Analysis, Henry Boyd, “excluding the Naval Infantry battalion in the Crimea, which was effectively captured wholesale, the

Ukrainian Armed Forces lost between 15% and 20% of their pre-war D–30 inventory in combat operations.”

Russian disinformation operations are currently a cornerstone of the country’s efforts to wield influence worldwide. Whether trying to weaken the EU, NATO, individual countries, or other groups, Russian operations perpetrated by cyber-espionage groups such as APT28 and APT27 have fostered anxiety, fear, and division throughout the world. Disinformation efforts have their roots in “active measures”, or propaganda efforts invented by the Soviet Union and embraced by the current Russian foreign intelligence services. Russian disinformation operations were credited with sowing discontent in the United States and damaging Hillary Clinton’s electoral chances in 2016; boosting support for far-right Italian political parties among those consuming alternative news stories in 2018; and prompting a decline in the Spanish leaders’ ability to influence public opinion during the 2017 Catalan crisis. In a CSIS article “Did Russia Influence Brexit?”, Russian cyber influence operations in the UK are elaborated on:

The UK Government is accused of making a deliberate effort not to find out how Russian influence may have affected the June 2016 vote. This is more incredulous because the government admits there was Russian interference in the 2014 Scottish referendum, declaring it the first time that Russia directly interfered in a Western election. The government also admits that Russia interfered in the [UK] December 2019 general election.

In a 2019 article in the New York Times, it was revealed that “In interviews over the past three months, the officials described the previously unreported deployment of American computer code inside Russia’s grid and other targets as a classified companion to more publicly discussed action directed at Moscow’s disinformation and hacking units around the 2018 midterm elections.” This was a significant cyber response akin to the 2012 “AC/DC” Thunderstruck attack on the Atomic Energy Organisation of Iran. It certainly is a creative way of letting your adversary know that even after the Stuxnet attack of 2010 the organization is still vulnerable to cyber-attack. The tepid American response of using the Department of Justice “naming and shaming” in the form of indictments of Russian government cyber operators has not been effective in dissuading cyber-attacks.

The US response to Russian 2018 election inference illustrates the complexity of signalling an adversary in a connected era. To be credible, signals of the possible use of force need to be backed by a reputation for resolve and sufficient capabilities to achieve the desired effect. In this case, Russia needs to know the US is willing to shut down the power to Moscow, to St. Petersburg, and key military installations. Washington certainly has the capability, but the question of resolve is not as clear-cut. In fact, one must ask: What Russian action would really push the US to shut down power and cripple civilian as well as military facilities in a nuclear-armed state’s territory? Would the US really run the risk that Russia might view the power cuts as the precursor to a pre-emptive strike? Thus, it is unclear whether the signalling effort described in the Times article worked. Such actions demonstrate a capability to access a rival state’s network, but not necessarily the resolve or ability to carry out more devastating cyber operations.

There are real concerns about whether cyber operations are a sufficiently costly signal or even the right instrument of power to coerce rivals. Previous studies have found cyber operations can compel rivals, but only when used in conjunction with other instruments of power. What is clear, is since 1999 under the right circumstances cyber operations can advance the foreign policy goals of Russia, engage the Russian public to maintain support for Putin, destabilize the global economy and inflict economic loss, undermine democracies and the transition of power, leverage partisan legal and social issues for societal dissention, assist and support allied regimes in their internal and external struggles and create a “force-multiplying” capability for military operations. Russian cyber capabilities are incredibly diverse and continually evolving.