ThreatConnect identifies Chinese targeting of two European drone and energy companies. Economic espionage or military intelligence?

It was the best of times; it was the worst of times. While Russian advanced persistent threat (APT) activity against the US and other international organizations has dominated the headlines recently, Chinese APT actors have been active outside the limelight. In June 2016, Chinese APT actors were discovered using a customized implant within the network of a European consumer electronics company that specializes in drone technologies and a U.S. subsidiary of a French energy management company that builds infrastructure for the U.S. government and the Department of Defense. Chinese efforts against the European consumer drone company appear to be economically motivated and represent a deviation from the September 2015 agreement between the U.S. and China to disavow economic espionage. Due to their involvement with the U.S. military, it could be argued targeting the energy management company was for military intelligence and not economic espionage.

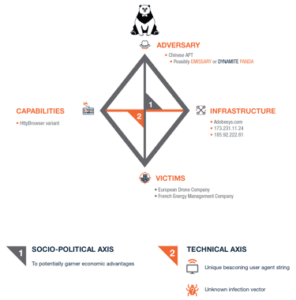

Using the Diamond Model of Intrusion Analysis, we will start by walking through the technical axis of the attack where we found malware used by multiple Chinese APTs calling back to a domain with the same registrant as those used in the 2015 Anthem and OPM breaches. We’ll pivot to the socio-political axis of the attack, and discuss how the victims fit the targeting profile of at least one Chinese APT – although we are unable to attribute the attack to a specific Chinese APT at this time.

Capabilities: HttpBrowser backdoor

On June 08, 2016 ThreatConnect identified a malicious executable MD5: 3BEA073FA50B62C561CEDD9619CD8425. This malware is a variant of “HttpBrowser”, a backdoor used by multiple Chinese APTs, including EMISSARY PANDA (aka APT27/TG-3390) and DYNAMITE PANDA (aka APT18/Wekby/TG-0416). Some reports refer to HttpBrowser as the GTalk trojan or “Token Control.” According to TrendMicro, HttpBrowser allows a threat actor to spawn a reverse shell, upload or download files, and capture keystrokes on a compromised system, similar to other remote administration tools (RATs). Antivirus detection for HttpBrowser is extremely low and typically based upon heuristic signatures. The report also indicates HttpBrowser is not available on underground markets.

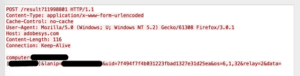

Several variants of the HttpBrowser backdoor exist; however, in this particular sample beaconing network traffic stands out as the telltale “HttpBrowser/1.0”. The User-Agent string is replaced with “Mozilla/5.0 (Windows; U; Windows NT 5.2) Gecko/%lu Firefox/3.0.1”, where %lu is a format modifier that appends an unsigned long numerical data type to the user-agent string.

The malware sends system information using the query string “computer=<COMPUTER NAME>&lanip=<LAN IP>&uid=<Unique ID>&os=<OS VERSION>&relay=<RELAY NUMBER>&data=<DATA>”

Infrastructure: Adobesys[.]com and a familiar registrant

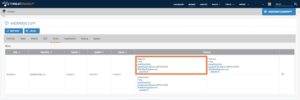

Leveraging ThreatConnect’s WHOIS function, we identified the malware’s hardcoded command and control domain adobesys[.]com was registered by the Chinese domain reseller and mass registrant, li2384826402[@]yahoo[.]com. This email address is infamous for registering domains used in the DEEP PANDA-attributed Anthem and OPM attacks in 2015, and provides additional evidence tying this HttpBrowser activity to Chinese APT actors.

Using ThreatConnect’s Farsight Passive DNS integration, we can identify the adobesys[.]com domain was hosted at two IP addresses — 173.231.11[.]24 and 185.92.222[.]81 — while the domain most likely was operational. One other domain, newsoft2[.]com, was hosted at the 185.92.222[.]81 IP during the same timeframe as adobesys[.]com. WHOIS information indicates that newsoft2[.]com was also registered by a Chinese registrant (omyname@gmail[.]com), and its co-location with the malicious adobesys[.]com domain suggests that it may be operated by the same actors behind the HttpBrowser activity. Indicators from this activity have been shared in incident 20151228A: Chinese HttpBrowser Activity Targeting European Companies.

Victims: two targets

We provided a lead on the malware and adobesys[.]com to a partner, who collected associated network traffic and worked with us to analyse the activity. In this case, the activity was targeted against only a few companies. We determined the Chinese actors used the “HttpBrowser” backdoor variant to target a control systems engineer in product development at a European consumer drone company. The traffic also helped us identify another target: the U.S. subsidiary of a French energy management company that has contracts with the U.S. Department of Defense and other U.S. government elements to implement energy management and SCADA solutions.

Both organisations were alerted to this activity shortly after it was discovered. At this time, we have no indication what, if any, data was stolen from them.

Adversary: pondering the PANDAs

While we cannot state for certain which Chinese APT is behind this activity, targeting a consumer drone company and energy management company is most consistent with previous EMISSARY PANDA targeting. Both EMISSARY and DYNAMITE PANDA have previously targeted the defense and aerospace industries, among others; however, EMISSARY PANDA is the only one of the two known to have targeted energy companies. According to the Secureworks report, EMISSARY PANDA commonly conducts strategic web compromises (SWCs), also known as watering hole attacks, on websites associated with the target organisation’s industry to increase the likelihood of compromising victims with relevant information. EMISSARY PANDA also uses spearphishing emails to target specific victims. At this time we do not know whether SWCs or spearphishing emails were used to target the victim organisations.

Socio-political: discussing possible motivations

The HttpBrowser sample piqued our interest since the information security community has had a heightened focus on whether or not Beijing is abiding by the September 2015 agreement between U.S. and China to disavow economic espionage. The U.S. subsidiary of the French energy management company looks like an artful dodge. These dual use organisations – those that possess significant intellectual property and are also involved with the U.S. government – present tempting targets for China that could facilitate a variety of espionage efforts. However, China could claim such activity constitutes military espionage and therefore does not violate the agreement between Presidents Obama and Xi from last September.

By contrast, targeting the European civilian drone maker looks like a case of economically motivated espionage. The world’s largest and most popular drone manufacturer is China’s DaJiang Innovation Technology (DJI), which currently holds about 70% of the commercial drone market share and was valued at over $10 billion in May 2015. The emerging global market for business services using commercial drones was recently valued at over $127 billion due to the growing applicability of drones across industries including agriculture, mapping, and surveillance.

In this instance, China most likely is seeking to quash any competition posed to DJI’s command of the market. Within the command and control traffic we were able to identify that a control systems engineer — with probable access to the European firm’s proprietary drone intellectual property and technical data — was targeted as a part of this activity, which likely further demonstrates the motivation behind the operation. With access to the targeted company’s intellectual property, sensitive communications, and product roadmap, China could provide its favored companies with economic advantages such as:

- Integrating competitors’ unique or proprietary capabilities: Many commercial drones rely on custom software for capabilities such as stabilisation, tracking, and GPS. Stealing and integrating competitors’ technologies would lessen any advantage that competitors would have over Chinese drones.

- Preempting competitors’ innovations:Leveraging compromised intellectual property on drone innovations could allow Chinese companies to advance their own product lines beyond what competitors plan to introduce in future products.

- Preempting financial or pricing moves from competitors: In an industry where price wars and gouging can have a significant impact on the competition, having the inside scoop on how your competitors plan to price their drones can provide an upper hand in attempting to undercut them and steal market share.

- Understanding competitors’ business and development plans or bid efforts: Insider information on how competitors plan to expand their business, augment manufacturing, market their product, or bid contracts, can all help Chinese drone companies gain an advantage over their competitors.

Economic espionage evolution?

While Chinese cyber-enabled economic espionage may be less pronounced, it almost certainly hasn’t ended and likely has evolved to help solidify leading market shares. In some ways, solidifying the dominant Chinese firm in a market feels like the next chapter in economic espionage. The overarching storyline of China’s economic espionage has been targeting strategic industries and allowing China to catch up with established champions. Chinese APT efforts against American Steel manufacturers likely facilitated the rise in Chinese world steel production from about 15% in 2000 to 50% in 2015.

China may be attempting to avoid the ire of the U.S. government as it targets organisations that are headquartered elsewhere. Furthermore, China may also be attempting to be more efficient as it focuses collection on organizations that meet multiple intelligence requirements. Targeting such organizations could allow China to explain away their activity as non-economic espionage, thereby adhering (with their fingers crossed) to the Rose Garden agreement.

[su_box title=”About ThreatConnect” style=”noise” box_color=”#336588″][short_info id=’84141′ desc=”true” all=”false”][/su_box]

The opinions expressed in this post belongs to the individual contributors and do not necessarily reflect the views of Information Security Buzz.