Regions of the world in geopolitical turmoil, like Turkey, are prime targets for cyber espionage campaigns. Starting in mid-November, an unknown actor purporting to be from the tax collection arm of the Turkish government began a spear phishing campaign against a Turkish defense contractor. The group used tactics that have become extremely useful for cyber spies—spear phishing emails that social engineer the victim to download an attached or embedded file and then enable macros. These macros contain executable files that download a Remote Access Trojan (RAT), which can log keystrokes, take screenshots, record audio and video from a webcam or microphone, and install and uninstall programs and manage files.

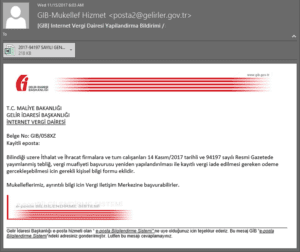

RiskIQ identified multiple employees within the targeted organization that were affected. The first email we were alerted to was sent on November 16 at around 6 a.m. The email, which we censored from victim PII, looked like this:

Fig-1 Example of the spear phishing email

Analysis – Stage 1 Email Attachment

The email supposedly comes from the Turkish government entity responsible for taxes. The email states that there is a possible tax exemption in place for the receiver if he/she fills out the attached documents. Although the sender domain, gerlirler.gov.tr, is valid, if we check the actual email SPF verification, we can see that it failed:

Received-SPF: Fail (domain gelirler.gov.tr does not designate 185.85.204.180 as a permitted sender),

client-ip=<185.85.204.180>; identity=<posta2@gelirler.gov.tr>; helo=<lnx1.hostingfabrika.com>;

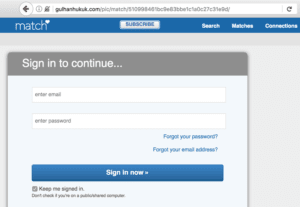

Proprietary data within RiskIQ PassiveTotal shows the IP sending the email messages hosts a law firm website: https://community.riskiq.com/projects/d731e758-cc96-b68e-4286-fe8b8f2308f1?guest=true:

Fig-2 Site for a law firm also hosted on the IP from which the emails came

While it could, of course, be a fake website, it’s more likely a compromised host as it also contained phishing pages for the dating website Match.com:

Fig-3 A phishing page also hosted on the IP

Normal email for the Gelirler domain would come from the IP specified in the MX record of gelirler.gov.tr, which is 212.133.164.130. Their SPF records, which enforce this process, have been set to “v=spf1 mx -all.”

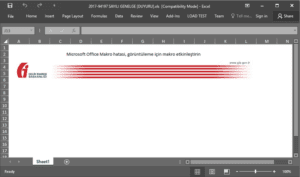

The attachment is an XLS document with the title “2017-94197 SAYILI GENELGE [DUYURU].xls.” Opening the document shows a prevalent attack flow: Macros.

Fig-4 Malicious attachment encouraging the user to enable macros

The Turkish text above the image translates to: “Microsoft Office Macro error, enable macros for viewing,” a message that social engineers the user to enable macros.

The macro contains a slightly obfuscated malicious executable file inside. The executable data is stored inside the macro in the form of arrays with integer values spread throughout the macro script. The data from the arrays is combined and written to disk in the Application Data folder. The filename chosen seems to be random for every macro—most likely generated automatically.

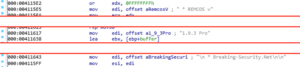

Fig-5 The arrays as seen in the macro, converting the values shows a stripped PE header.

In the XLS shown above, the PE is written to %appdata%\brqco.exe and executed. This file is a small (3kb) loader, which downloads the second stage of the attack. The loader has no imports, but at runtime, resolves the UrlDownloadToFile function from the URLMON library to download stage two, and then ShellExecute from kernel32 to run the downloaded stage two. The stage-two payload downloads from hxxp://unifscon[.]com/R9_Sys.exe.

Analysis – Stage 2 RAT

Stage two of the attack is a packed piece of malware, and the packer used is Visual Basic-based. After the malware unpacks, it carries the unmistakable leftover information pointing to a RAT known as ‘Remcos’—specifically, it seems, the paid Pro version:

Fig-6 Stage two of the attack

Remcos is a tool supposedly sold for ‘remote administration’ purposes, but like many of these services, it’s used in digital attacks often. Current Remcos functionality includes:

- File operations: download, upload, modify, and search for files on infected machines

- Screen reading: automated screenshotting of the infected machine

- Registry operations: full control of the registry

- Interaction functionality: an operator can open a chat session with the victim

- Steal or modify the clipboard

- Execute (VBS) scripts or executables

- Tasks (automate any of the above functionality to run periodically)

- Use infected hosts as SOCKS5 proxies (direct and reverse, allows for tunneling and proxying)

More information on Remcos, additional reference samples, unpacked samples, and write-ups can be found on Malpedia: https://malpedia.caad.fkie.fraunhofer.de/details/win.remcos

One interesting piece of functionality is the SOCKS5 proxy capabilities. An operator can turn the victims of the crime into proxies for its own network, hiding the real C2 server. We can see the operator do this in this campaign.

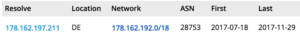

The C2 server configured for the attack on the defense contractor is civita2.no-ip.biz. RiskIQ has also seen civita1.no-ip.biz used in other samples of the same campaign (more on this later). While the emails started appearing around mid-November, the operator had a C2 server in place already—a rented server at Leaseweb. We can see the server first appear in DNS routing on July 18:

Fig-7 Resolution info for the C2 server used in the attack

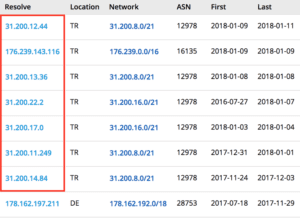

Then, a little while after sending out the spear phishing emails, we can see the IP resolution change with, most likely, IP addresses of compromised machines used for SOCKS5 proxying to hide the C2:

Fig-8 IP resolution info for the c2 server changing

While almost all IP addresses are under AS12978, which is a Turkish broadband IP pool, the only one other IP address in the list is 176.239.143.116, which comes from a Turkish mobile connection.

The odds are that the listed IP addresses belong to victims turned into SOCKS5 proxies or a single victim with predictably good uptime. The first IP address we noticed was most likely the C2 server at which they started. It’s possible that the actors are still using it, but have hidden it behind the SOCKS5 proxies of their victims.

Analysis – Additional Infrastructure and Malware Samples

One interesting aspect of this campaign is that the C2 domain formats are clearly numbered in civita[0-9]+.no-ip.biz format. We found one more set like the previous one on shared IP space, which follows the komot[0-9]+.punkdns.pw pattern:

Fig-9 C2 following the same pattern

This set of domains also comes back if we investigate the domain used to spread the initial RAT from the unifscon.com domain. Here is a list of filepaths and the configured C2:

| unifscon.com filepath | C2 |

| /R9_Sys.exe | komot1.punkdns.pw:5700 |

| /Favos.exe | civita2.no-ip.biz:4042 |

| /NWConn.exe | civita1.no-ip.biz:8484 |

| /R9_Sys7.exe | komot1.punkdns.pw:7500 |

Something to note is that the initial URL from which the stager would download a payload, located at unifscon.com/R9_sys.exe, changed payloads often during our research. This lead to a lot of overlap in the infrastructure of the attack linking the four domains we’ve mentioned together.

The full set of discovered samples based on the distribution domain and the C2 domains can be found in our RiskIQ Community project listed in the next section. Additionally, for those with VirusTotal Intelligence dashboard access, we suggest close monitoring of the following submitter ID: 2c5391fa. This Russia-based submitter seems to be a pre-leading cause to a lot of samples we see appearing online in VirusTotal—some uploads are WinRAR SFX self-extracting containers or just plain samples.

Indicators of Compromise (IOCs)

The indicators of the campaign (IOCs) targeting the defense contractor can be found in the table below. Keep in mind that while the IP addresses listed on the network IOC section aren’t all the IP addresses to which the domain pointed, they are only the IP addresses to which the host pointed during the campaign described above.

We would also like to point out that this campaign wasn’t run on its own—far before this campaign, the actors used these domains in other attacks. Pivoting through the related IP addresses can give some additional insights into the vast infrastructure of this attacker, which seems to be relying on using its victims as the SOCKS5 tunnels’ proxies.

Additional IOCs based on expanding our search criteria and pivoting on the C2s yielded a very large set, which is available (combined with the IOCs for the defense contractor) in our RiskIQ Community Project: https://community.riskiq.com/projects/d731e758-cc96-b68e-4286-fe8b8f2308f1?guest=true

Filesystem IOCs

| SHA256 | Note |

| 70b1a96ca6a9cf93a9945bec1f0c2ff793c2f34f5c9aa9f975f5386a6467bb8c | Stage 1 Excel document with macro |

| fa606bfc64fb2940a423610ebd41ff79eac67c74059a4120d1583e88550b13b7 | Stage 1 Excel document with macro |

| 8483e94c60b90898dd9677b080ec664d63c43d0978c0bb871c6f2b04cb6c9a12 | Stage 1 Excel document with macro |

| 9aa8dd5141166ee252ab61d3e518e5730ffe8fd2acfd8cd820f990d20bc468a2 | Stage 1 Excel document with macro |

| fa27d7833b743d1960fdd51a5a250f6869835bb7560a4eb9d61f32d590c2ab60 | Stage 2 Loader |

| 07fdd507deff1680361b7106298575d0128983173d3670e5b830d8566190c39a | Stage 2 Loader |

| ac3a2db520592abe8497abf2db14bb3a2468e11768b4585cc1ffc057971aac3d | Stage 3 RAT |

| eb367f22531f2346898c1f9bca69b8f03742bee5aa4fec51f29f5fd9520a446f | Stage 3 RAT |

| 0ca47d69249b42f2a7b2a60e4fbd2058a70b6d43eee549ab5ea31523289da09a | Stage 3 RAT |

Network IOCs

| Domain | IP Address |

| civita1.no-ip.biz | 178.162.197.211 |

| 31.200.14.84 | |

| 213.183.40.59 | |

| civita2.no-ip.biz | 31.200.14.84 |

| 31.200.11.249 | |

| 31.200.17.0 | |

| 31.200.13.36 | |

| 176.239.143.116 | |

| 31.200.12.44 | |

| komot1.punkdns.pw | 212.7.208.121 |

| 136.0.3.219 | |

| 213.183.40.59 | |

| komot2.punkdns.pw | 213.183.40.59 |

For a full, continuously updated list of IOCs related to this attack, visit the RiskIQ Community Public Project here: https://community.riskiq.com/projects/d731e758-cc96-b68e-4286-fe8b8f2308f1?guest=true

[su_box title=”About Yonathan Klijnsma” style=”noise” box_color=”#336588″][short_info id=’102864′ desc=”true” all=”false”][/su_box]

The opinions expressed in this post belongs to the individual contributors and do not necessarily reflect the views of Information Security Buzz.