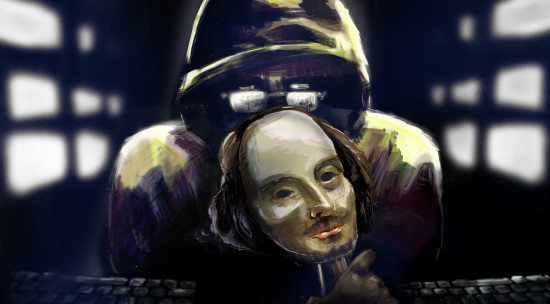

A gang of Shakespeare-quoting criminal computer nerds stole millions from British banks online. Cyberpolice carried out a global operation to stop the heist. Can they catch those responsible?

Act I: DISCOVERY

Gal Frishman scours the Internet looking for things most people try to avoid — malicious bits of software sent out to spy or steal. On Aug 25, 2011, sitting at his desk in Tel Aviv, he found something he’d never seen before.

It was a banking Trojan, designed to sneak into a computer and drain your bank account. This one had peculiar survival instinct. It could hide or play dead, giving the impression it had been deleted only to re-install itself later.

“They had some really innovative stuff,” Frishman said. He got to work, thrilled to be the first malware researcher to lay eyes on a new species. Soon he noticed something even weirder. Broken fragments of Shakespeare, from The Merchant of Venice, were buried in the program files.

Give me your blessing I am Launcelot your boy.

Over the next few days Frishman and his colleagues at the computer security company Trusteer went into what they call “combat mode,” working morning-till-night to unravel the malware and map its DNA. They published a report in September and named their discovery Shylock, after the vengeful money lender from Shakespeare’s play.

What made Shylock so dangerous was the way it defied attempts to remove it, according to Adrian Nish, London-based head of cyberthreat intelligence at BAE Systems Applied Intelligence, who spent years studying it. “It was able to resurrect itself,” he said.

By 2014, Shylock had infected more than 100,000 computers, mostly in the U.K., but also in the U.S. and Italy. The malware was transferring millions of pounds a year from unwitting bank customers to the Russian-speaking gang of computer nerds who created it. A BAE Systems report in 2013 called Shylock “one of the most sophisticated and fastest growing threats posed by cybercriminals today.”

Even though it was a fraction of the estimated $400 billion a year lost to online crime, the scale of the heist got the attention of law-enforcement agencies. Senior officials from the FBI and the U.K. National Crime Agency met in late 2013 and decided that, since most of the victims were British, the NCA should lead the effort to wipe out Shylock.

NCA cyber specialist Paul Hoare was chosen to run the operation. A stout former detective, Hoare has hooded eyes that narrow when he talks about online thieves. “I’m not going to say I have a grudging respect for them,” he said in an interview at the NCA. “They are organized criminals.”

Hoare decided the best way to destroy Shylock was to attack from several angles at once. He called in police from U.S., U.K., Germany, the Netherlands, France, Poland and Turkey, and contacted Microsoft Corp., since the malware used its operating system.

Operation Disputed, the first malware takedown led by Europeans, began on July 8, 2014, at Europol’s headquarters in The Hague, Holland. This is its story.

ACT II: TAKEDOWN

The operation’s success hinged on cutting off the criminals from Shylock for long enough to wipe it out. Malware strains need to evolve to survive. They do this by constantly calling out to computer servers used by criminals to send instructions and updates.

Hoare and his team at Europol planned to seize those servers and block the web domains that allowed them to talk to infected PCs.

Because the gang registered hundreds of domains around the world, it would be difficult to wrest away control. Some were U.S.-based .coms, others were .su from the old Soviet Union. A few ended .cc, meaning they were set up in the Cocos Islands. Shylock’s creators thought (wrongly) police couldn’t reach a registry in the tiny island cluster off the coast of Australia.

After several hours of nerve-wracking delays, at about 7 p.m., Hoare got the confirmation he was waiting for from Seattle. Microsoft had served court orders on U.S. domain registry VeriSign Inc. directing that all Internet traffic to Shylock’s American domains be diverted to a Microsoft “sinkhole,” set up to gather data.

For the first time Microsoft’s digital crimes team could see how many infected computers were out there, and piped that information through to the Europol command center. The number was 130,000 and rising.

At 8 p.m., Hoare gave the order. A member of his team typed out a message on the operation’s internal communications system — “All law enforcement takedowns – GO.”

ACT III: TOASTERS AND KNITWEAR

With some online fraud, like lottery scams, victims are left wondering how they could be so stupid. Not Shylock. Its creators hacked into around 500 legitimate websites and used them to deliver the malware to anyone who visited.

The sites looked normal, selling the sort of stuff regular Brits like to buy: toasters, curry and Scottish knitwear. There were local sports teams, a politician and a blog about motherhood.

Once Shylock got inside a computer, it waited until someone tried to make an online bank transfer, then changed the destination so the gang got the money. The program had clever ways to distract attention. It would display seemingly helpful pop-ups warning of “unusual account activity.”

Shylock even altered the helpline number shown on a bank website. If a customer called to ask what was going on, they never reached the bank and instead got a chargeable line set up by the gang and a recorded message saying: “The person you are trying to reach is not available.”

ACT IV: WHACK-A-MOLE

Even as Hoare pressed go on Operation Disputed, the Shylock gang began to fight back. As fast as officers took down domains, the gang set up new ones.

The police and the criminals were still locked in an arm-wrestling match when Hoare left the control room and returned to his hotel at about 4 a.m.

His biggest problem: the team hadn’t been able to reach registries for the old Soviet Union sites, despite hours of trying. The .su domains were live and threatening to blow the whole operation.

Hoare snatched a few hours of sleep and was back at Europol at 7:30 a.m. the next day. The Soviet registries hadn’t responded. “The longer and longer that went, the more tense things got,” Hoare said.

Then Europol’s Paul Gillen came up with the idea of contacting Eugene Kaspersky, silver-haired founder of the world’s sixth-biggest security software maker, whose Moscow-based firm has special powers in Russia.

Kaspersky’s malware expert, Sergey Golovanov, was in the office at about 8 p.m. Moscow time when he got an urgent e-mail from his boss. Within two hours he had asked the Soviet registry to suspend 75 Shylock domains.

Kaspersky Labs “were very quick. Save-the-day quick,” said Gillen, who has since left Europol for Barclays Plc. “We started to get the upper hand again.”

Hoare finally closed the operations room at 9 p.m. on July 9. By the end of week, new domains stopped appearing. It looked as if the Shylock gang had given up.

ACT V: WANTED, THE SHYLOCK GANG

Operation Disputed virtually wiped out the Shylock malware in the wild. Hoare said the NCA hasn’t had any reports of losses from banks since. In May, Microsoft said it detected the program on about 11,000 IP addresses, a drop of more than 90 percent from last year.

About a month after Operation Disputed, Ukrainian police working with the FBI searched properties and seized computers in the country, according to special agent Keith Mularski, who supervises the bureau’s Pittsburgh-based cyber division.

The FBI and U.K.’s NCA said they were actively pursuing suspects and declined to give specific details. The Shylock gang, however, remains at large.

Most people agree they will strike again. Cyberthieves don’t just give up and get regular jobs, according to Golovanov, the malware expert at Kaspersky. “They are criminals, they are still free. They need to make money.”

It remains a mystery why the gang decided to scatter Shakespeare through the code. “I don’t know why they did it,” Europol’s Gillen said.

At least two other known malware strains have contained Shakespearean references. It could be the same gang is responsible, or it could be a trope among the hacking community.

Frishman, who discovered Shylock, was reminded of the early days of programming, when coders would leave something unique in their work — a calling card. “Maybe this was a relic,” he said.

[su_box title=”About Kit Chellel” style=”noise” box_color=”#336588″]

Kit Chellel is Experienced reporter covering legal, finance, crime and anything else. Byline stories published in the Boston Globe, Wall Street Journal, Sydney Morning Herald, Washington Post, Chicago Tribune, Die Welt, Irish Independent and others.

Kit Chellel is Experienced reporter covering legal, finance, crime and anything else. Byline stories published in the Boston Globe, Wall Street Journal, Sydney Morning Herald, Washington Post, Chicago Tribune, Die Welt, Irish Independent and others.

Breaking news, investigations and magazine features, 100 words-per-minute-shorthand. He can draw a nice picture too.Reporter in the legal team covering financial litigation, fraud, white collar crime and regulation. Lead reporter and writer for the Dow Jones Financial News website (www.efinancialnews.com), covering breaking news on London’s banks, asset managers and investment firms. Also provided news and features for the magazine (circ. 19,000) on investment banking and financial services.[/su_box]

The opinions expressed in this post belongs to the individual contributors and do not necessarily reflect the views of Information Security Buzz.