When the Necurs botnet went dark at the beginning of the month, so too did email campaigns bearing Locky ransomware and Dridex, prompting questions among observers about the reasons behind the pause and how long it would last. The second question now seems to be have an answer: on June 21, Proofpoint researchers observed the first multi-million message Locky email campaign since May 31st. On the evidence of reused IP addresses, this campaign appears to be originating from the Necurs botnet. As of the writing of this blog on June 22, a second, much larger Locky campaign was underway, signaling a clear return of both Locky and the Necurs botnet.

Just prior to the Necurs disruption, Locky authors had introduced new anti-sandboxing and evasion techniques. Those techniques are present in the new campaigns and are detailed below.

Email campaign

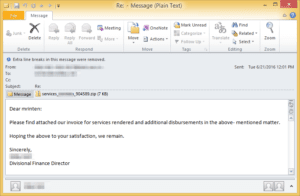

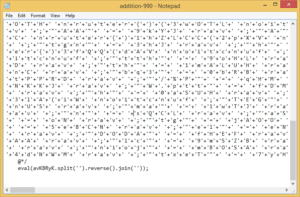

On June 21, Proofpoint detected a large Locky campaign with zip attachments containing JavaScript code. If opened, these attachments would download and install Locky with an Affiliate ID of “1” and DGA seed of 7743. The messages in this campaign had the subjects “Re:” with the attachment “services_[name]_[6 random digits].zip”, “[name]_addition_[6 random digits].zip” or “[name]_invoice_[6 random digits].zip”. The zip files contained JavaScript files named “addition-[random digits].js.”

Figure 1: Email delivering the zipped JavaScript distributing Locky ransomware

Figure 2: Obfuscated JavaScript attachment

Analysis

In late May, Locky added a new loader that implemented at least three new anti-analysis tricks. The first technique targets virtual machines (VMs) with poor maintenance of realistic processor timestamp counter values. The malware compares the number of CPU cycles that it takes to execute certain Windows APIs. As you would expect, it takes more cycles in a VM environment to execute most Windows functions. However, the increase is not uniform and some instructions take much longer than others, allowing malware authors to measure these ratios and detect virtualization.

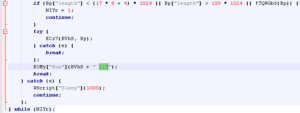

The second technique involves Locky’s execution from JavaScript. It is executed with the argument of “123”, which is converted to an integer within the loader’s code and used as part of its runtime obfuscation. In particular, this specific argument is required in order for some runtime-deobfuscated code in the loader to be deobfuscated properly. As this code is made writable and executable at runtime, failure to have the correct instructions in place will cause an exception resulting in termination of the malware. Dealing with this process interdependence may prove to be a problem for some analysis platforms.

Figure 3: JavaScript (after deobfuscation) launches the downloaded Locky loader with the argument “123”

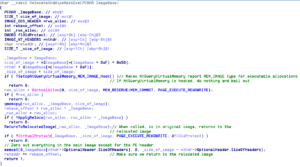

The third technique helps hide some secrets of the loader from cursory inspection and involves an interesting method of cross-module execution. Once the loader’s checks are complete, it unpacks the Locky binary via RtlDecompressBuffer and overwrites the original loader image. After performing some manual runtime loading, it executes the Locky binary’s entrypoint which eventually calls the function in Figure 4. This function checks for hooks on NtQueryVirtualMemory and, if none exist, hooks NtQueryVirtualMemory to fake that executable allocations are of the MEM_IMAGE type. It then creates a writable and executable copy of the Locky binary residing in the main executable, applies relocations to it, and then calls a function that modifies the saved instruction pointer to return to the relocated image. Since the saved instruction pointer to code in the main executable’s entrypoint still exists on the stack, it relocates that pointer as well before returning from this function. At this point, there is no use for the main executable, so it zeroes out everything in the function but the PE header, making manual analysis of memory dumps more difficult.

Figure 4: The third anti-analysis trick used by Locky involves an interesting method of cross-module execution

Conclusion

Although email message volumes in the June 21 campaign were just 10% of those observed before the Necurs disruption, this remains a very large campaign relative to those we have seen over the last three weeks. At the same time, the introduction of new anti-VM and evasion techniques in the Locky ransomware loader creates new challenges for analysts, sandboxes, and vendors attempting to detect and mitigate the latest version of Locky.

Analysis of the sending IPs associated with this campaign suggest that the Necurs spam cannon is functional again and, unfortunately, we expect both Dridex and Locky email campaigns to begin again in earnest. We are already tracking a much larger Locky campaign on the second day of operation and will continue to monitor the situation.

Indicators of Compromise (IOC)

| IOC | IOC Type | Description |

| 4292f8dbbd6823bf5693e52c79ac70b81a8d97e1a2f1b939c12a1170018c04c8 | SHA256 | addition-365.js email attachment |

| [hxxp://yourworshipspace[.]com/a3py3w] | URL | Locky payload URL |

| [hxxp://51.254.240[.]48/upload/_dispatch.php] | URL | Locky hard-coded C&C |

| [hxxp://185.82.216[.]55/upload/_dispatch.php] | URL | Locky hard-coded C&C |

| [hxxp://91.219.29[.]41/upload/_dispatch.php] | URL | Locky hard-coded C&C |

| [hxxp://217.12.223[.]83/upload/_dispatch.php] | URL | Locky hard-coded C&C |

| [http://kjvacahtvb.work/upload/_dispatch.php] | URL | Locky DGA C&C |

| [http://rhvpwqledatdxerrx.info/upload/_dispatch.php] | URL | Locky DGA C&C |

| [hxxp://sonuh5glplozcs2m[.]tor2web[.]org] | URL | Locky payment portal |

| [hxxp://sonuh5glplozcs2m[.]onion[.]to] | URL | Locky payment portal |

| sonuh5glplozcs2m[.]onion | URL | Locky payment portal (TOR) |

[su_box title=”About Proofpoint Inc.” style=”noise” box_color=”#336588″][short_info id=’60344′ desc=”true” all=”false”][/su_box]

The opinions expressed in this post belongs to the individual contributors and do not necessarily reflect the views of Information Security Buzz.