DDoS attacks have always been a major threat to network infrastructure and web applications.

Attackers are always creating new ways to exploit legitimate services for malicious purposes, forcing us to constantly research DDoS attacks in our CDN to build advanced mitigations.

We recently investigated a DDoS attack which was generated mainly from users in Asia. In this case, attackers used a common HTML5 attribute, the <a> tag ping, to trick these users to unwittingly participate in a major DDoS attack that flooded one web site with approximately 70 million requests in four hours.

Rather than a vulnerability, the attack relied on turning a legitimate feature into an attack tool. Also, almost all of the users enlisted in the attack were mobile users of the QQBrowser developed by the Chinese tech giant Tencent and used almost exclusively by Chinese speakers. Though it should be noted that this attack could have involved users of any web browser and that recent news could ensure that these attacks continue to grow — and we’ll explain why later in the article.

How They Did It

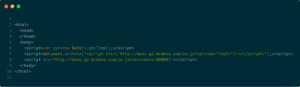

Ping is a command in HTML5 that specifies a list of URLs to be notified if the user follows a hyperlink. When the user clicks on the hyperlink, a POST request with the body “ping” will be sent to the URLs specified in the attribute. It will also include headers “Ping-From”, “Ping-To” and a “text/ping” content type.

This attribute is useful for website owners to monitor/track clicks on a link. Read more here.

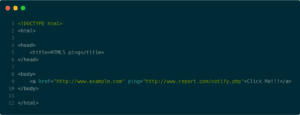

A simple HTML page containing a link with “ping” attribute

A simple HTML page containing a link with “ping” attribute

A POST request with the “ping” body

Notification services using ping are not new. The Pingback feature in the popular WordPress CMS notifies a web site owner if a link is clicked. Attackers have used Pingbacks to conduct DDoS attacks by sending millions of requests to vulnerable WordPress instances that are then forced to “reflect” the pingback requests onto the targeted web site.

Besides using the HTML5 ping, this DDoS attack also enlisted mostly mobile users from the same part of the world. While we’ve observed mobile browser-based attacks before, a DDoS attack mostly using the same mobile browser and from the same region is very uncommon.

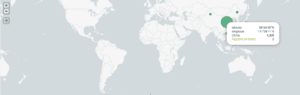

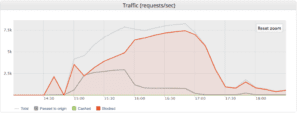

About 4,000 user IPs were enlisted in the attack, with a significant percentage from China. They generated a peak 7,500 Requests per Second (RPS) during the 4 hour attack, producing an overall 70 million requests.

Source IP location (mostly China) |

7,500 RPS during the 4 hour attack |

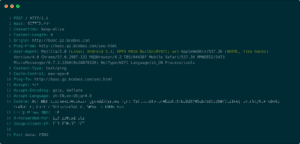

Diving into the logs to understand the attack, we noticed that all the malicious requests contained the HTTP Headers “Ping-From” and “Ping-To”. This was the first time we had seen a DDoS attack that utilized the <a> tag ping attribute.

Both Ping-Form and Ping-To values referred to the “” URL.

A sample of the requests that were generated by the DDoS attack

This suspicious URL contains a very simple HTML page with two external JavaScript files: “ou.js” and “yo.js”.

“” source code

“ou.js” had a JavaScript array containing URLs — the targets of the DDoS attack.

“OU.JS” JavaScript source code

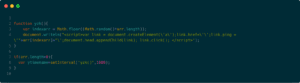

“yo.js” had a function which randomly selects a target from the array and creates a <a> tag with “ping” attribute pointing to the target URL.

Every second, a <a> tag was created and clicked programmatically causing a “ping” request to be sent to the target website.

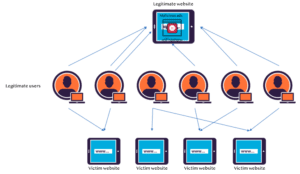

Legitimate users that were tricked into visiting this suspected website unwillingly participated in a DDoS attack. The pings will continue to be generated as long as the user stays on this page.

“yo.js” JavaScript source code

The question is: How did the mastermind keep users on this web site in order to keep triggering the ping requests and maintain the ferocious DDoS attack?

We noticed that the User-Agent in the requests is associated with the popular Chinese chat app, WeChat. WeChat uses a default mobile browser to open links in messages. As QQBrowser is very popular in China, many users pick it as a default browser for their smartphone.

Our theory is that social engineering combined with malvertising (malicious advertising) that tricked unsuspecting WeChat users into opening the browser. Here’s one possible scenario:

- The attacker injects malicious advertising that loads a suspected website

- Link to the legitimate website with the malicious ad in an iframe is posted to a large WeChat group chat

- Legitimate users visit the website with the malicious ad

- JavaScript code executes, creating a link with the “ping” attribute that the user clicks on

- An HTTP ping request is generated and sent to the target domain from the legitimate user’s browser

Final Words

While QQBrowser was overwhelmingly used in this DDoS attack due to its popularity with WeChat users, other web browsers can also be exploited by this ping attack. Worse, the browser makers are taking steps to make it harder for users to turn off the ping feature in their browser that would allow them to avoid being enlisted in such an attack.

According to an article earlier this week in Bleeping Computer tech news site, newer versions of Google Chrome, Apple’s Safari and Opera no longer let you disable hyperlink auditing, aka pings. This is a concern for web architects and security pros worried about this method of launching DDoS attacks spreading.

Fortunately, web site and application operators have some control. If you are not expecting or do not need to receive ping requests to your Web server, block any Web requests that contain “Ping-To” and/or “Ping-From” HTTP headers on the edge devices (Firewall, WAF, etc.). This will stop the ping requests from ever hitting your server. (Note: Imperva DDoS Protection is already updated to prevent ping functionality abuse targeted at your sites.)

Application DDoS attacks are here to stay and will continue to evolve at incredible rates. Attackers are always finding new and creative ways to abuse legitimate services for malicious purposes. At Imperva, we are dedicated to detecting and combating these threats on your behalf.

The opinions expressed in this post belongs to the individual contributors and do not necessarily reflect the views of Information Security Buzz.